The real story of money

What mainstream macroeconomics told you about money is a lie. They overwhelm you with complex equations and statistical jargon to distract you from asking the most important question: where does money come from, and where does it go?

Money

Money is credit. Full stop. Don’t let anyone tell you otherwise. Don’t let central bankers confuse you with their fictional monetary aggregates. Banks create money through the act of lending. When a bank issues a loan of $100,000, it creates an asset (the loan) and a matching liability (the deposit) on its balance sheet:

Table 1. Individual bank’s balance sheet after lending.

| Assets | Liabilities |

|---|---|

| Loans: + $100,000 | Deposits: + $100,000 |

Thus, banks create money when they make loans to customers (Werner, 2014). The money is not “moved” from existing depositors’ accounts. Banks do not wait for savers to deposit before lending—they create savings through lending. Banks are not intermediaries—they are the primary creators of money.

Central banks also create money through asset purchases, commonly known as quantitative easing (QE). For example, when the Fed implements $100 billion in QE, the balance sheets of various economic agents are affected as follows:

Table 2. Central bank’s balance sheet after QE.

| Assets | Liabilities |

|---|---|

| Securities: + $100 billion | Reserves: + $100 billion |

Table 3. Non-bank institutions’ balance sheets after QE.

| Assets | Liabilities |

|---|---|

| Securities: - $100 billion | No change |

| Deposits: + $100 billion |

Table 4. Banks’ balance sheets after QE.

| Assets | Liabilities |

|---|---|

| Reserves: + $100 billion | Deposits: + $100 billion |

Post-QE, the total quantity of money in the form of deposits increases by $100 billion. The newly created money itself is not backed by anything tangible—papers backed by papers. They simply swap whatever debt securities owned by the general public into so-called money, which the banks record as deposits. The money is created at will and assigned to actors who already own securities—i.e., the rich.

Historically, however, commercial banks create far more money than central banks. The Bank of England estimated that 97% of the money in circulation was created by commercial banks (McLeay et al., 2014), while the central bank accounts for only 3%.

So why do we have these monetary aggregates, such as M0s and M3s? They were invented to distract you from knowing who actually creates money, to whom they give it, and for what purpose. The “M” might as well stand for “misleading.” Central banks usually publish credit data on their websites, but they obscure its true significance. Ultimately, it’s the private banking sector and the central banks, allocating credit in ways that shape economic outcomes—who gets rich, who stays poor, which industries flourish, and which starve.

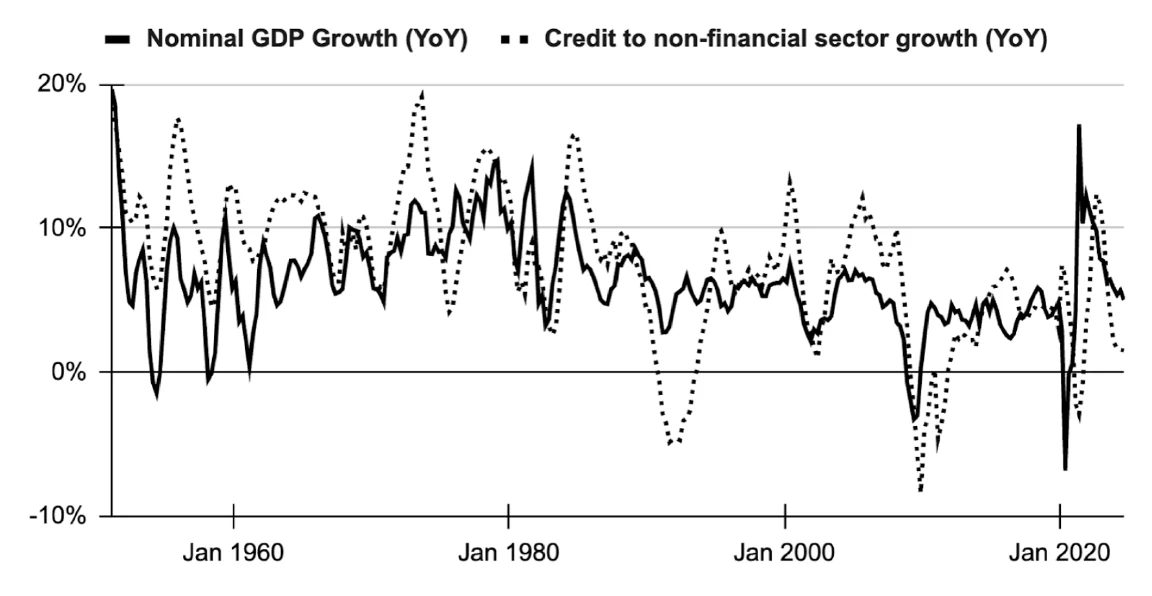

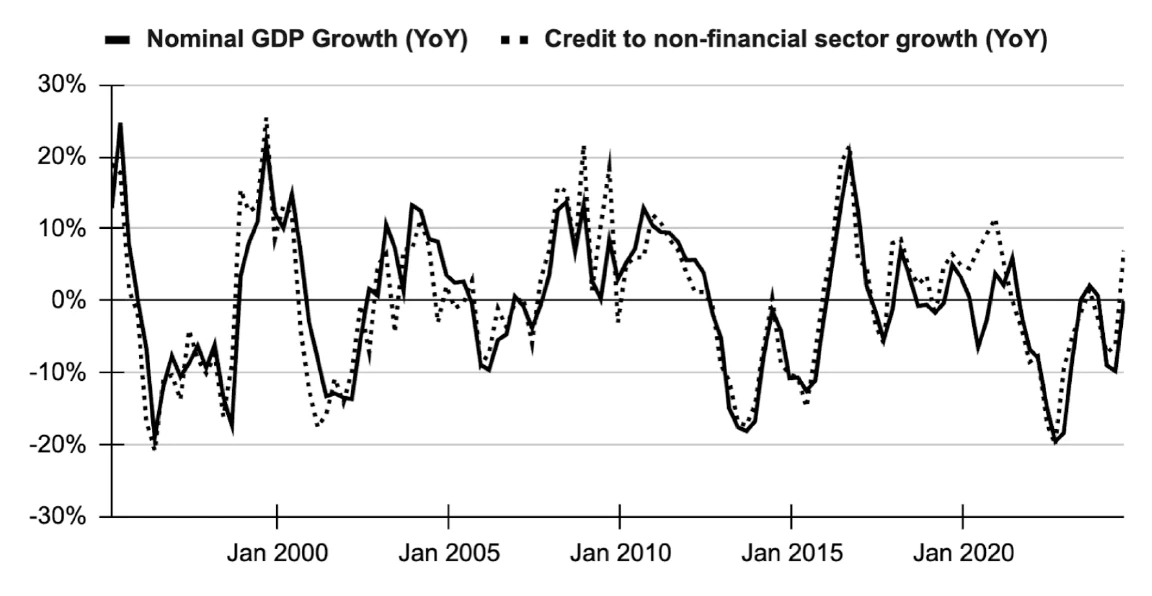

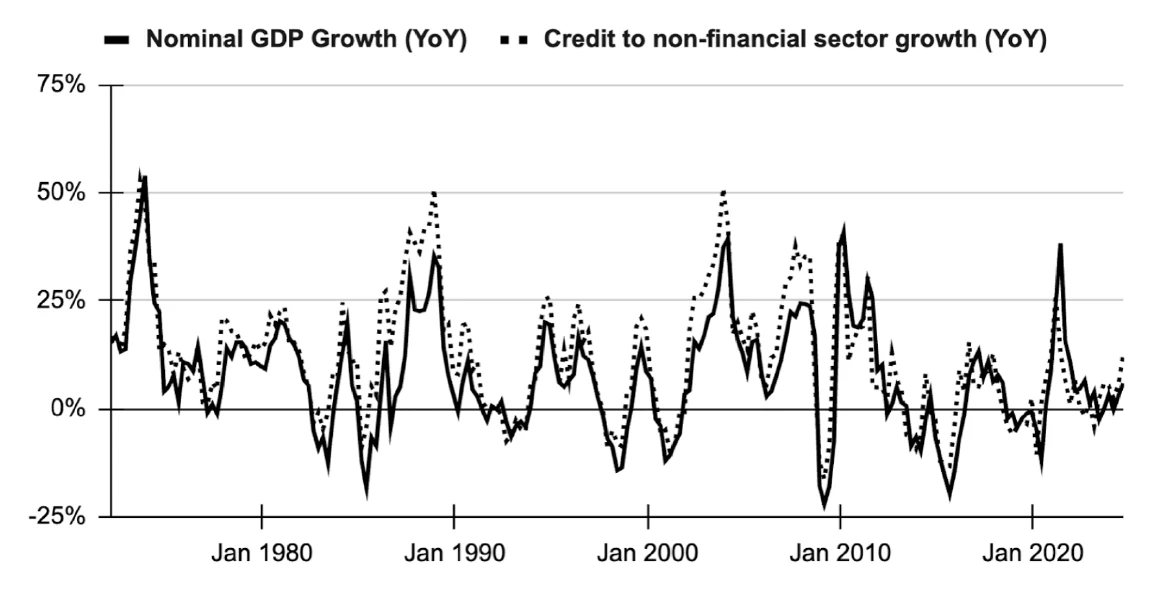

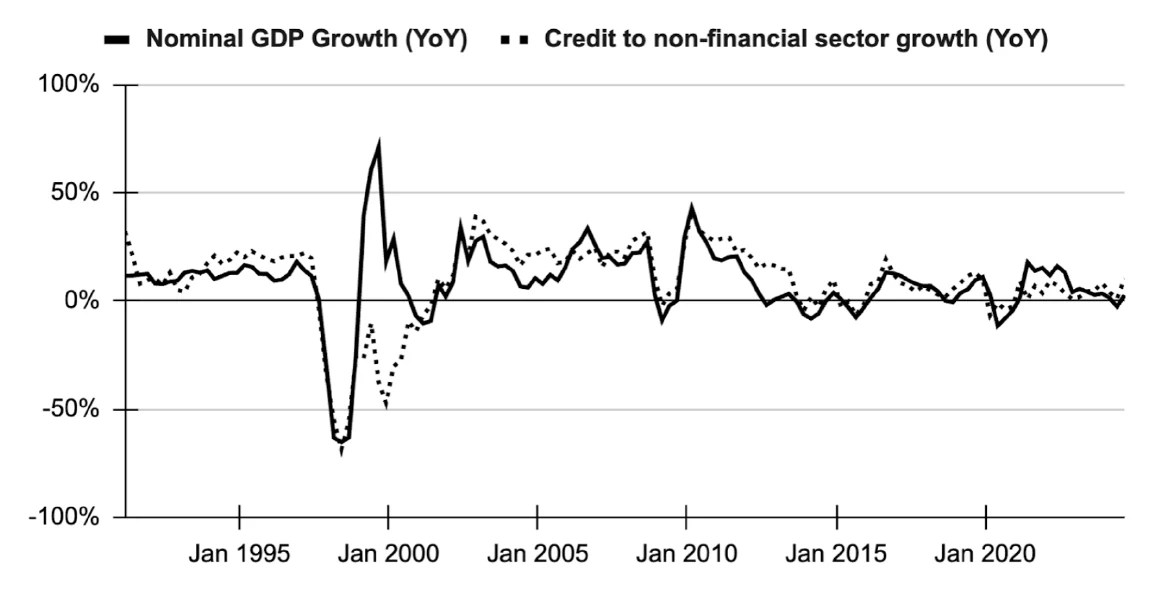

Money serves as a tool to acquire capital, goods, and services, which will be discussed in the subsequent sections. The rate at which money is created determines whether we’re in a boom or bust. To whom the created money is given determines whether we get inflation or growth.

Prices

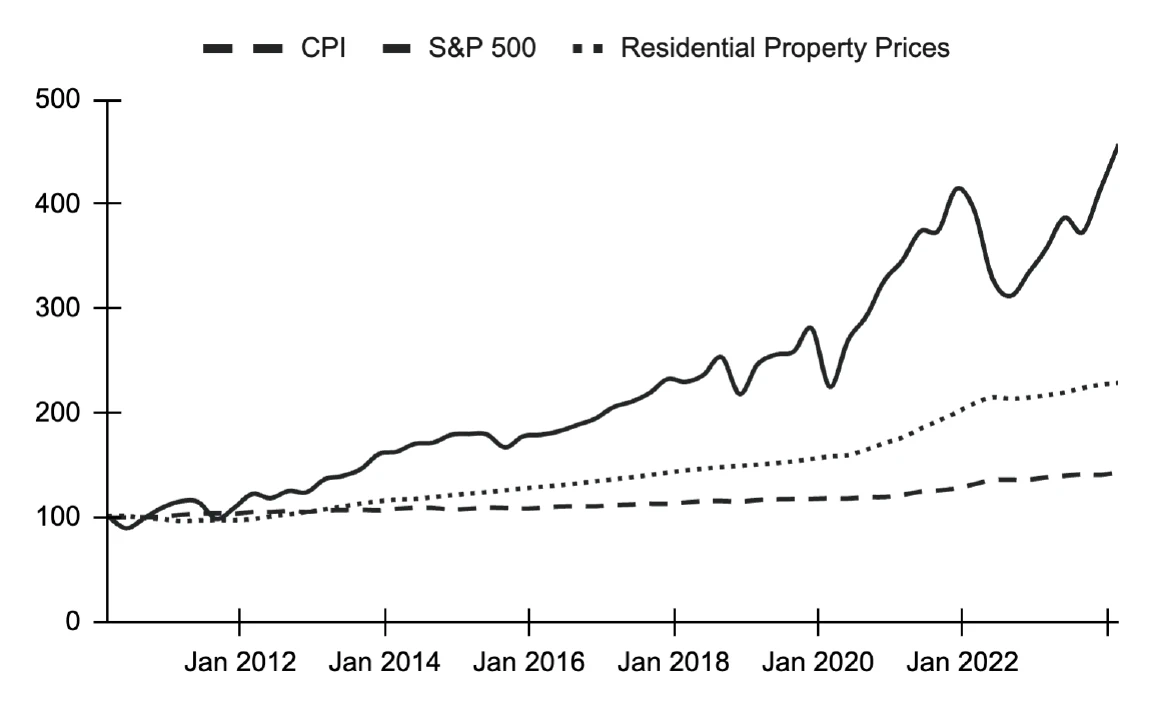

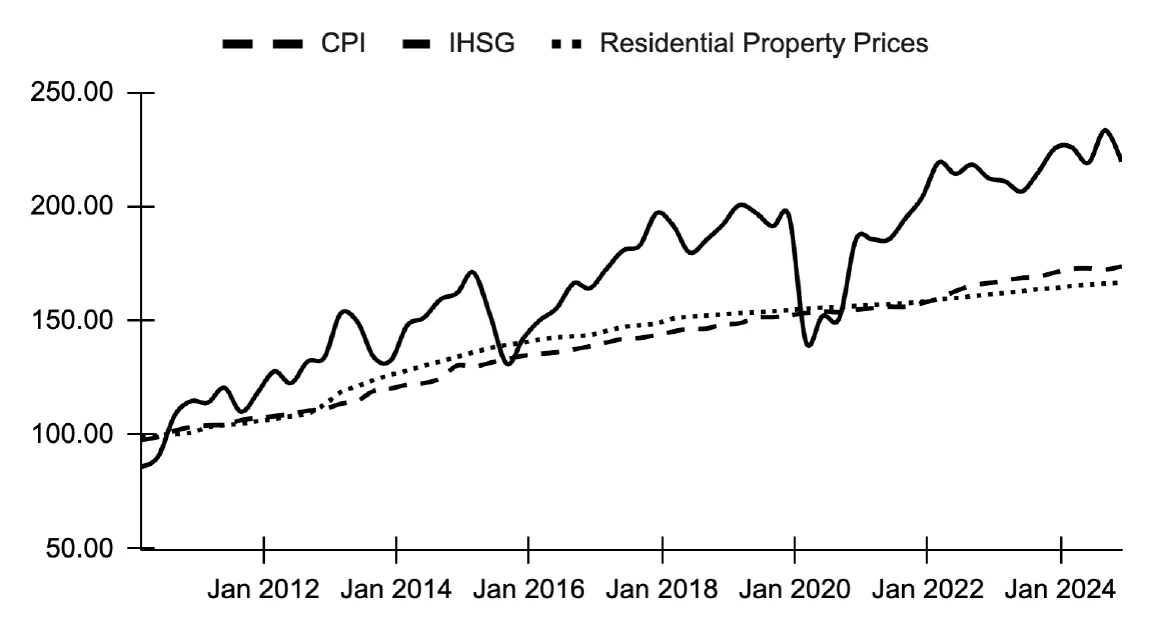

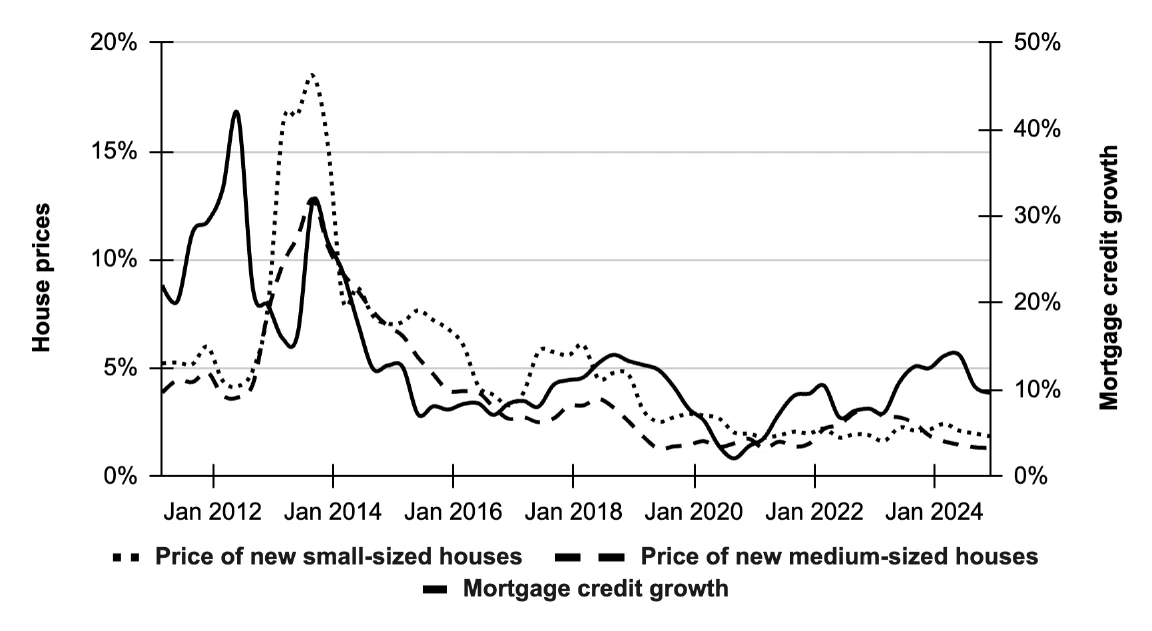

Prices are the amount of money needed to acquire anything money can buy. This includes capital (both financial and real capital, which will be discussed in Section 5), goods, and services. The consumer price index tells you only half of the story (Alchian & Klein, 1973). The measurement of prices must account for all things money can buy—stock prices, real estate, and more. If food costs stay flat while house prices double, government officials will point you to the consumer price index and claim that “prices are under control.” But for anyone trying to buy a house, reality screams otherwise.

Inflation

Inflation measures the rate at which prices change over time. It results from money creation outpacing the economy’s ability to produce goods, services, and capital. Friedman (1963) famously said, “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.” He was right, just not in the way mainstream economics interprets it. Excluding asset prices from headline inflation masks the effects of money creation.

Quantitative easing didn’t make bread and milk more expensive. It raised stock prices, real estate values, and other financial assets. When credit creation is directed toward financial markets—leveraged buyouts, exotic derivatives, rapid property flipping—it creates localized asset price bubbles without immediately affecting consumer prices. Eventually, though, that money will flood grocery stores or car dealerships, but no one knows exactly when or where it will happen.

Redefining the word “inflation” is necessary to understand how money creation causes prices to rise. The official inflation statistics are a smokescreen, hiding the true costs of money printing and enabling banks and central banks to operate without public scrutiny. Until asset prices are fully accounted for (Goodhart, 2001), the inflation targeting framework adopted by central banks around the world is nothing but a shit show.

Goods and services

Goods are tangible items consumed or used; services are activities performed for you. The total value of goods produced and services provided in a country over a specific period is reported as gross domestic product (GDP). Since goods and services are purchased with money, bank credit creation directed toward GDP-related transactions directly increases GDP (Werner, 2005).

Capital

Capital is an asset used to accumulate wealth. Capital can be tangible, like land, or intangible, like stocks. Capital may appreciate and depreciate in value and it may provide streams of income for the owners. There are two types of capital: financial and real capital.

Financial capital is a contract backed solely by the promise of future returns, either through value appreciation, cash flows, or both. This includes stocks, bonds, derivatives, and countless others. I shall refer to the rate of return on financial capital, calculated as the expected appreciation plus the total streams of cash flows, as the rate of interest.

Real capital consists of tangible or intangible resources used to produce goods and services, such as machines, factories, or land. I shall refer to the rate of return on real capital as the rate of profit.

Table 5. Financial vs real capital

| Characteristics | Financial capital | Real capital |

|---|---|---|

| Examples (tentative) | Stocks, bonds, and derivatives. | Machines, factories, and land. |

| Rate of return | Interest | Profit |

| Owners | Speculators | Entrepreneurs |

The term “interest rates” here is slightly different from what you might expect in economics textbooks or conversations. You might have heard that interest rates are inversely related to bond prices. This is not always true in practice. Speculators often pay very little attention to the bond coupons; they only care about the price at which they could sell the bonds in future dates relative to the price at which they acquired them. Thus, interest rates may be positively correlated with bond prices.

The classification of an asset as financial or real capital depends on the purpose of its acquisition. Land purchased for speculation is financial capital; land purchased for farming is real capital. This distinction hinges on use, not form, making formal empirical measurement challenging. However, common sense suffices to differentiate the two in practice.

Financial capital often, but not always, funds real capital. For example, when a firm issues a bond to build a factory, the bond is financial capital, while the factory is real capital. The distinction between financial and real capital matters for two reasons. First, their values may diverge. Stock and bond prices can plummet overnight, but the factories and machines they fund remain intact. Second, their rates of return differ. If a company projects a 20% profit rate for a factory, no rational investor would demand an interest rate exceeding 20%, as the company could not cover the difference.

Thus, the rate of interest must be regulated by the rate of profit and should not consistently exceed it. If interest rates surpass profit rates, the system resembles a Ponzi scheme. Investors get rich on paper, but no real wealth is created. Only real capital could produce a sustainable stream of income. Eventually, financial capital fails to meet its expected returns, investors panic, and the system collapses.

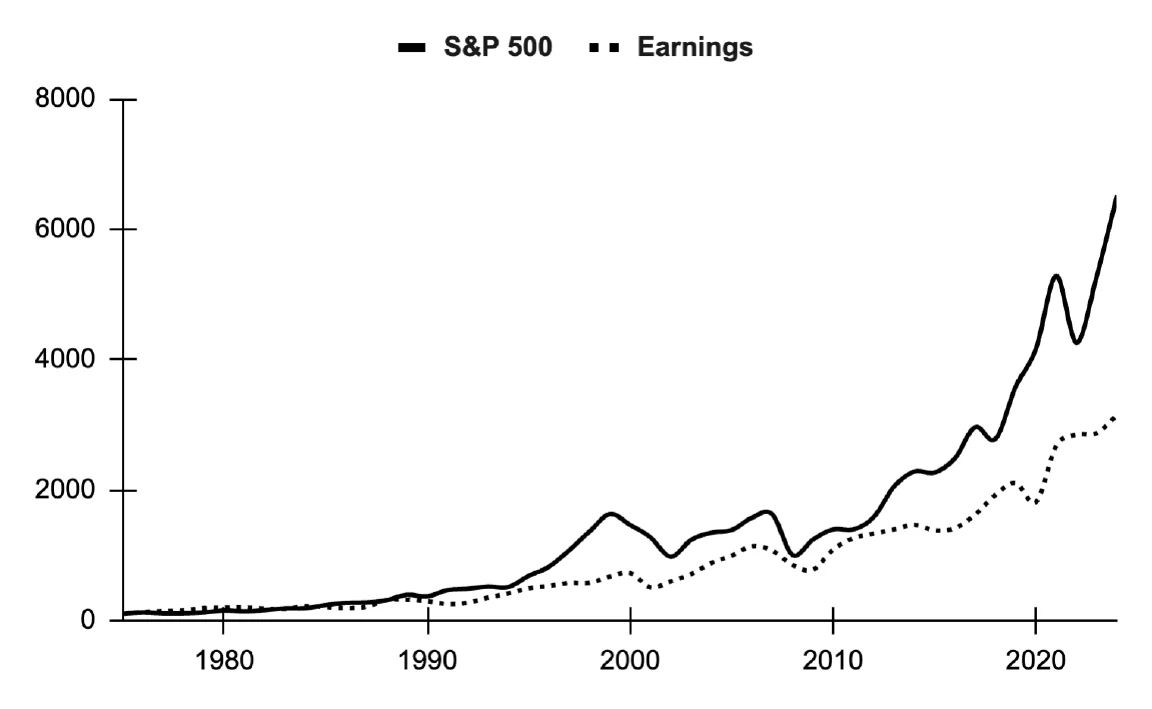

The situation worsens when financial capital funds additional financial capital through “financial innovation,” such as margin trading, short selling, or mortgage-backed securities. This increases the volume of financial capital without expanding real capital. As financial innovation becomes rampant, the financial sector becomes detached from reality—stock prices soar, but fundamentals lag. Financial sector profits surge, while the real economy struggles.

Credit creation towards the financial sector fuels booms, inflating financial asset prices, but the profit rate of real capital cannot keep pace. This explains why such booms inevitably end in busts. Shuffling papers is far easier than running a factory.

Labor

Labor is the time spent using capital to generate returns for capital owners. The number of people engaged in this process is called employment, which is divided into two: financial employment and real employment. Financial employment involves financial capital, such as brokers, bankers, and investment managers. Real employment operates real capital to produce goods and services, including factory workers, farmers, and engineers.

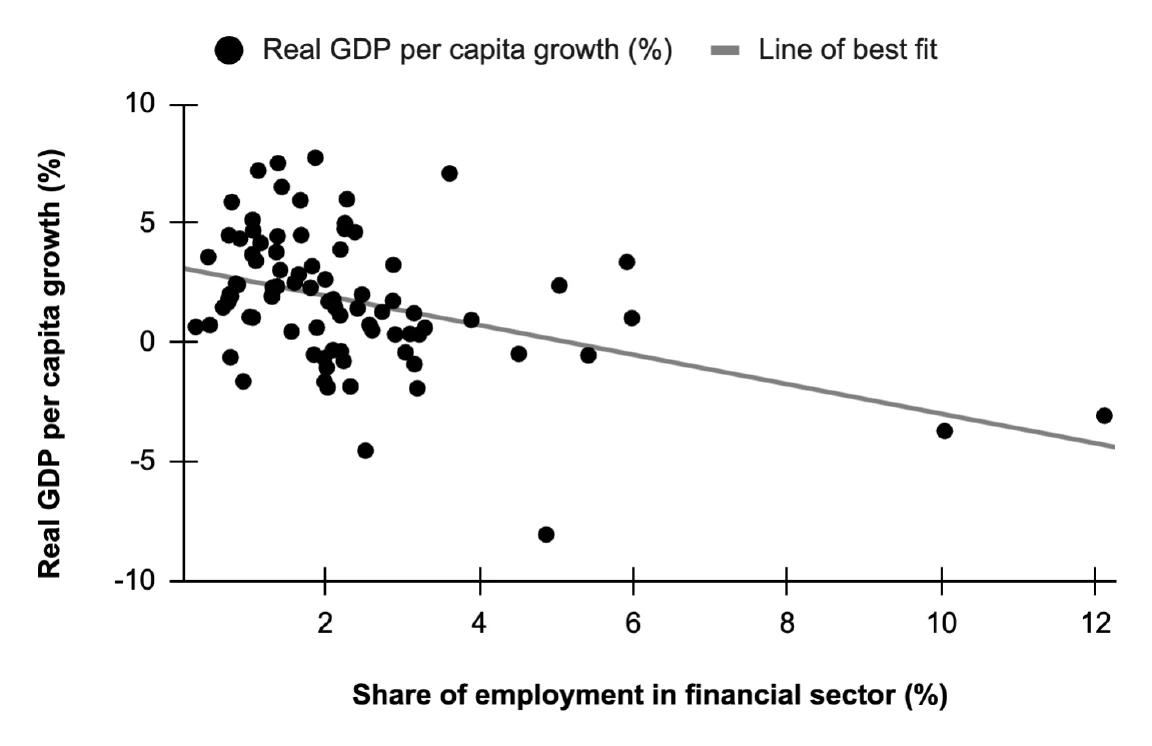

Official employment statistics often obscure the divide between unproductive “bullshit jobs” (Graeber, 2018) that shuffle papers and genuinely productive work. The rise of financial employment, which extracts value out of society without creating goods, signals economic decay (Figure 9) and exacerbates inequality.

This outcome reflects who receives credit and how they use it. If banks fund factories, real jobs grow. If they fund financial instruments, we get more MBAs betting on derivatives. Credit allocation shapes labor markets, and it’s currently favoring extraction over production.

Exchange rates

Domestic banks create money in local currencies, while foreign banks create money in foreign currencies. Most countries nowadays allow money to flow freely across borders. These movements of money determine the exchange rates—the value of one currency relative to another.

A currency appreciates when its value rises against other currencies, driven by money flowing into the country through sales of goods, services, or assets. Conversely, a currency depreciates when its value falls, caused by money flowing out through purchases of goods, services, or assets.

Sales and purchases of goods and services are recorded as trade balance, while capital transactions appear in a country’s balance of payments. Both are influenced by money creation, which, in turn, affects exchange rates. When banks and central banks create money without increasing production capacity, firms and households may purchase foreign goods, services, or assets. Conversely, if domestic production exceeds domestic demand, the country may export its goods, services, and assets.

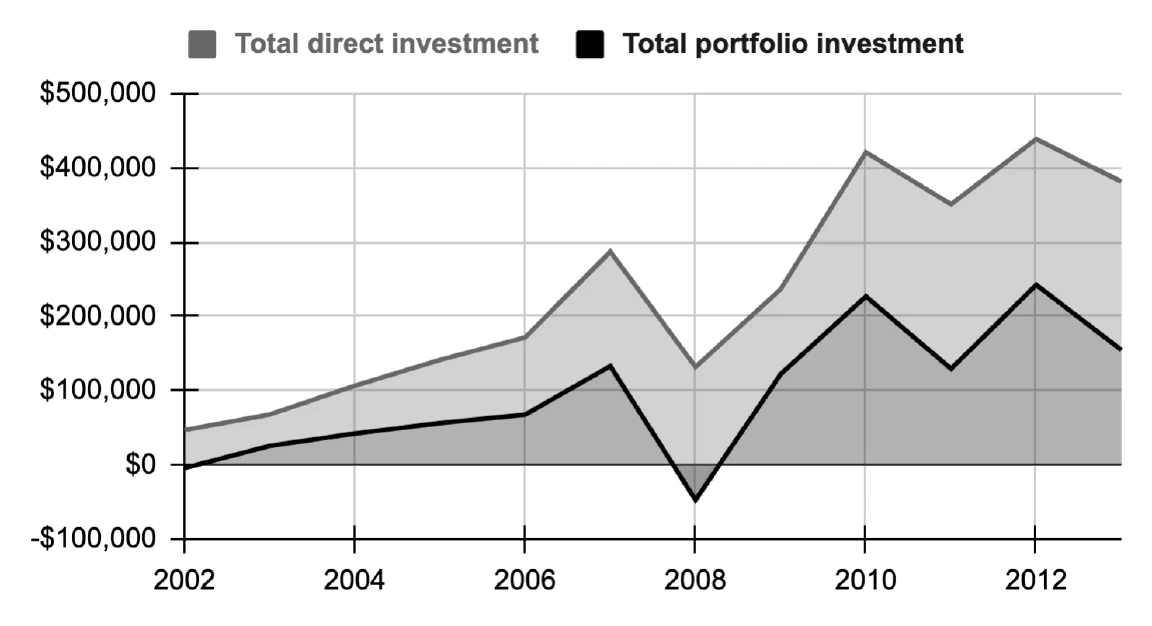

For example, following the global financial crisis of 2008, the Federal Reserve injected trillions of dollars into the financial system to revive the economy from a recession. This policy has two profound implications. First, real capital profit rates fell as U.S. consumers reduced spending. This makes investing in U.S. firms unattractive. Second, QE lowered the rate of return on safe assets like the U.S. Treasuries. This forces U.S. investors to seek higher returns overseas, turning to emerging markets in Asia and Latin America (Figure 10).

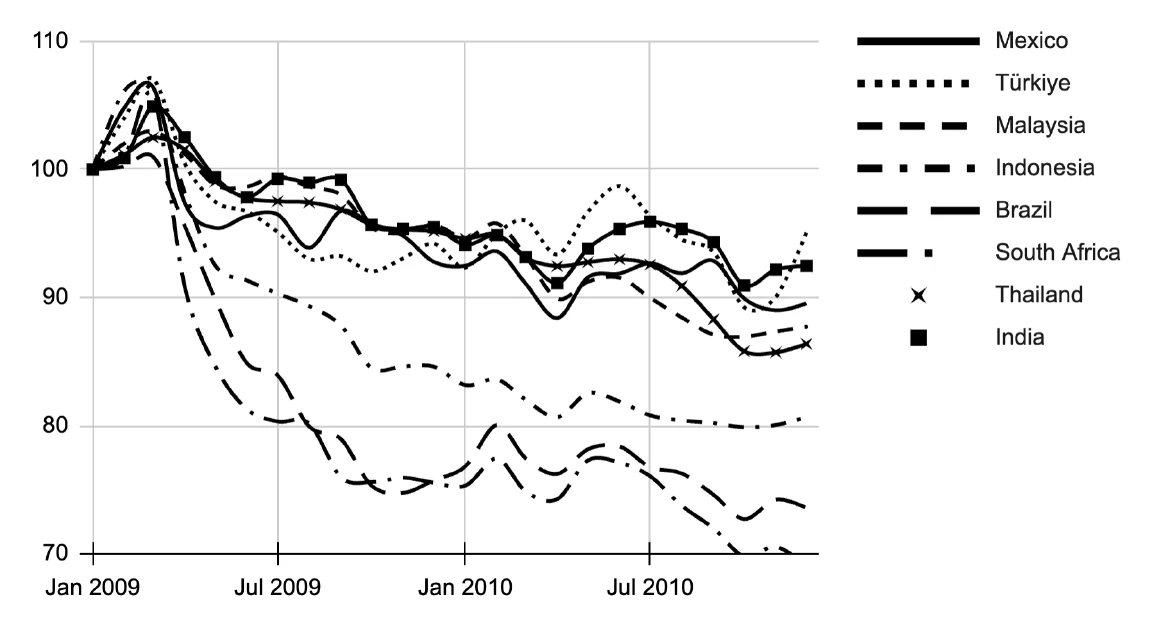

As a result, capital flows from the U.S. into emerging markets, appreciating their currencies against the U.S. dollar (Figure 11). Exchange rates reflect money movements through trade and capital flows, which are influenced by money creation. The rate of domestic money creation relative to foreign money creation signals future exchange rate trends.

Conclusion

Money is at the center of all macroeconomic questions. Banks are not intermediaries—they are the creators of money. And what they do shapes the current state and future paths of the economy. It determines which prices go up. It explains why certain industries flourish while others starve. It answers why capital and labor are concentrated in certain sectors.

Credit creation towards consumption expenditures causes consumer prices to rise. This applies to firms, households, and the government. Those government deficits financed by the banks, that car loan you applied for, that smartphone you bought using Paylater, those groceries you pay with your credit card, it all causes the prices of goods and services to rise because the bank prints new money for you and the government while the economy’s capacity to produce goods and services remains unchanged.

Credit creation for financial capital inflates the value of financial instruments. This “boom” in the financial sector increases demand for financial labor to shuffle papers and disincentivizes people to work in the real sector, reducing the economy’s capacity to produce goods and services. Meanwhile, the increasing demand for financial capital may raise the rate of returns on financial capital, the interest rates. When interest rates exceed the profit rates of real capital, investors get rich on paper, but no new real wealth is created. The system eventually collapses.

Credit creation for acquisitions of real capital increases the economy’s capacity to produce goods and services. This rise in real capital also increases the demand for real labor to operate the real capital, causing real employment to rise. Money affects real variables not because prices are sticky, but because it enables entrepreneurs to innovate, making production of goods and services more efficient, and access resources (real capital and labor) that would otherwise be unavailable to them (Schumpeter, 1911). Investments are not constrained by savings because savings are created when banks authorize firms to invest through credit creation.

As money flows across borders, it influences the prices at which currencies are exchanged. Money flows in and out of a country through sales and purchases of goods, services, and assets, respectively. The relative pace at which money is created compared to other countries signals the future paths of exchange rates. Currencies tend to depreciate when domestic money creation outpaces foreign money creation.

Watch these two indicators closely: (1) the rate at which the banking system creates credit, and (2) to whom that credit is granted. Mainstream economics overlooks these indicators, and not by accident. The bankers prefer to keep it that way to maintain their political influence over society.

References

Alchian, A. A., & Klein, B. (1973). On a Correct Measure of Inflation. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.2307/1991070

Goodhart, C. (2001). What weight should be given to asset prices in the measurement of inflation? Economic Journal, 111(472). https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0297.00634

Graeber, D. (2018). Bullshit Jobs: A Theory. Simon & Schuster.

McLeay, M., Radia, A., & Thomas, R. (2014). Money Creation in the Modern Economy. Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin, Q1.

Schumpeter, J. (1911). The theory of economic development.

Werner, R. A. (2005). New Paradigm in Macroeconomics: Solving the Riddle of Japanese Macroeconomic Performance. Palgrave Macmillan London. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230506077

Werner, R. A. (2014). Can banks individually create money out of nothing? - The theories and the empirical evidence. International Review of Financial Analysis, 36(C). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2014.07.015

Data sources

- Figure 1 and 2:

- Figure 3:

- Figure 4, 5, 6, and 7:

- Figure 8:

- Figure 9:

- Figure 10:

- Figure 11:

Tags: Economics